TYRE, Lebanon — Rabab Sadr Charafeddine recalls the hot August day 27 years ago when her brother boarded a plane for Libya.

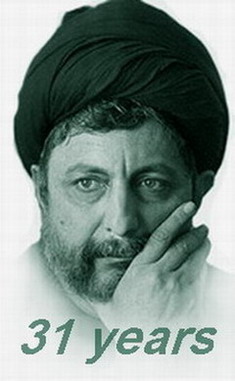

Musa Sadr, a revered cleric in southern Lebanon credited with reviving the historically oppressed Shiite Muslim population in his country, was leaving to meet President Moammar Gadhafi to discuss funding for the civil war that had engulfed Beirut.

The imam prepared a carry-on bag full of the books he loved to read, climbed into a navy Oldsmobile, and dashed off to the airport even as lack of sleep and the Ramadan fast slowed him down.

His sister hasn't seen him since.

It is widely believed among Lebanese that Gadhafi assassinated Sadr after a feud over money, and sent an imposter to Rome with the imam's suitcase and passport. The Libyan government has not shed any light on his disappearance, saying only Sadr left Libya for Italy — alive. An investigation has since exposed that claim.

The family has not given up, insisting abduction charges be brought against the Libyan president.

At the family's urging, the attorney general in Lebanon recently indicted Gadhafi and 17 others allegedly involved in the disappearance. A hearing has been set for March 16, although no one expects Gadhafi or his aides to show up.

The case is entangled in issues of foreign relations and economic repercussions, involving everything from arms development to the export of apples, all while revealing the tenacity of a Shiite population that lost a beloved leader.

If nothing else, the case holds great symbolic significance, representing a journey out of compliance and self-contempt for a Shiite population that once had little political voice in Lebanon. It is a path similar to what Iraqi Shiites could take after the country's national elections on Sunday.

In the 1980s, tensions between Libya and the West increased because of Gadhafi's foreign policies and terrorism, and his country's coziness with the Soviet Union.

The United Nations imposed sanctions on Libya after it was implicated in the 1988 bombing of Pan Am flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, which killed 270 people. The country faded into political and economic isolation.

In 2003, Libya accepted responsibility for the bombing, and the sanctions were lifted.

A few months later, Libya announced plans to dispose of its weapons of mass destruction, and began cooperating with the United States and the international community.

Fouad Ajami, who wrote The Vanished Imam on Sadr's life and the Shi'a of Lebanon, believes the recent investigation became a way for Lebanon to remind the world of crimes committed by Libya as it tried to plea bargain its way out of trouble.

"For the Shi'a, it's about being victimized by the Arabs. And it's about the feeling that here is this prominent leader who is liquidated to the silence of the rest of the Arab world," said Ajami, a Shiite Lebanese whose book describes Sadr as a savvy reformer whose critics panned him as an Iranian intelligence agent.

"It is about holding the system of power in the Arab world responsible for a great crime."

The Shi'a have come of age, and reactivating the case is a way of asserting a newfound political power, he said.

Some here say Libya's new role on the international stage will make it even more difficult to solve Sadr's case as any hope of outside pressure on Gadhafi to reveal information dissolves.

They show disdain for U.S. leaders who they say are only concerned with the Lockerbie victims, not with those whose fate is still unknown.

"Had Musa Sadr been a Westerner, we would have known what happened to him," said Farid el Khazen, political science chairman at the American University of Beirut.

Sadr's vision and philosophies have materialized into social institutions — vocational schools, health clinics and literacy centers around the country. His work spawned a new terrain in Lebanon, leading to creation of the armed political party Amal, which later yielded a splinter group called Hezbollah, a fighting militia.

Sadr, and later, the Shiite fundamentalist group Hezbollah, brought money, weapons and social services to a people with a history of political submission.

The country is now a stark contrast to its condition in the late 1970s, when there was no functioning government to effectively investigate such a crime, let alone one with prominent Shiite leaders.

Sadr helped conduct a national study surveying the deprivation of the South, populated by Shiites. The study showed roads had been neglected, no running water and little interest in building schools and hospitals because of the area's proximity to fighting near the Israeli border.

He lobbied the government to act and collected his own funds from nongovernmental organizations and private donors. He helped eliminate hunger by arming beggars with vocational job skills.

Currently, 1,150 students study at the Imam Sadr Foundation in Tyre, one of many institutes Sadr founded. Most of the students attend for free. The foundation's medical clinics in the South receive about 42,000 visits a year.

The 49-year old cleric stressed that the woman's role in society is equal to the man's, even taking on an unusual load of child-rearing responsibilities for his time. He was carefree at times, but also was known as an obsessively clean dresser who would eat chicken off the bone with a knife and fork.

As a child, Sadr would often travel with his father to a village in Iran, the family's native country, to help administer medicine for eye allergies and other ailments at a makeshift clinic.

As a spiritual leader in Lebanon, he worked to create a dialogue between warring Christians and Muslims, stressing the acceptance of other religions.

His family recalls the story of how a Christian ice cream vendor once came to Sadr complaining of a damaging rumor. People were saying Christians were dirty and Muslims should not buy his ice cream, the vendor said.

After Friday prayer services, Sadr plopped down in front of the vendor's shop and began eating ice cream.

Up until his death, the vendor is said to have cried at the mention of the imam's name.

Every year, public gatherings are organized in Lebanon to protest Libya, whose population is Sunni Muslim, and call for the return of Sadr. Periodically, political leaders will issue statements against Gadhafi, who responds by refusing to buy apples from Lebanon, one of the country's biggest export crops, Khazen said.

And the imam's legacy is sometimes invoked by politicking office holders trying to endear themselves to a Shiite population.

Some, including Sadr's sister, have not given up hope that the imam is still alive and imprisoned.

It was shortly after his departure that day in 1978 that Charafeddine began to worry.

A tall bearded man, with green eyes somewhere between the color of honey and olive, Sadr told his sister he wouldn't be long and left for the airport.

But her brother, who traveled frequently around the Middle East, never called home to say he had arrived at his destination as he had done unfailingly in the past.

"You don't want to believe the worst," said Charafeddine, who had helped pack her brother's suitcase that day.

A journalist and a sheik who accompanied Sadr also disappeared.

Charafeddine says she can't imagine Sadr is anything but alive and well. Any other news would force her into a difficult confrontation.

"It might prove to be like judgment day for me and the rest of the country," she said.

In Tyre, not far from the Imam Sadr Foundation that Charafeddine now runs, Hassan Bazzoun, 43, relaxes at an outdoor table at the Al-Boussi cafe.

Bazzoun and his companions say Sadr helped transform the lives of Shiites in the South. They point to his commitment to education, culture and a peaceful coexistence with Christians.

"The South and the Shi'a were one thing, and after Musa Sadr came, they became something else," he said, stroking the prayer beads in his hand.

"It was like going from the abyss to the light."

In the Shiite doctrine, there are 12 imams, or successors to the Prophet, the last of whom disappeared in the late 870s.

To this day, Shiites await his return, a time when they believe justice will be brought to earth.

If they one day were to find out that Sadr is indeed dead, they would be ready, Bazzoun said.

In the meantime, they are prepared to do something they do well.

"The Shi'as have a history of waiting," he said.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment